Page 108 - 6688

P. 108

108

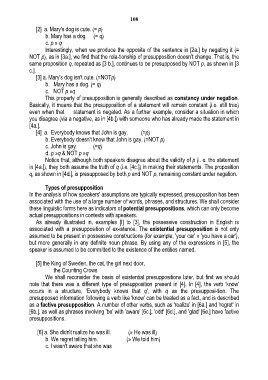

[2] a. Mary's dog is cute. (= p)

b. Mary has a dog. (= q)

c. p » q

Interestingly, when we produce the opposite of the sentence in [2a.] by negating it (=

NOT p), as in [3а.], we find that the rela-tionship of presupposition doesn't change. That is, the

same proposition q, repeated as [3 b.], continues to be presupposed by NOT p, as shown in [3

c.].

[3] a. Mary's dog isn't cute. (=NOTp)

b. Mary has a dog. (= q)

c. NOT p »q

This property of presupposition is generally described as constancy under negation.

Basically, it means that the presupposition of a statement will remain constant (i.e. still true)

even when that statement is negated. As a further example, consider a situation in which

you disagree (via a negative, as in [4b.]) with someone who has already made the statement in

[4a.].

[4] a. Everybody knows that John is gay. (=p)

b. Everybody doesn't know that John is gay. (=NOT p)

c. John is gay. (=q)

d. p »q & NOT p »q

Notice that, although both speakers disagree about the validity of p (i. e. the statement

in [4a.]), they both assume the truth of q (i.e. [4c.]) in making their statements. The proposition

q, as shown in [4d.], is presupposed by both p and NOT p, remaining constant under negation.

Types of presupposition

In the analysis of how speakers' assumptions are typically expressed, presupposition has been

associated with the use of a large number of words, phrases, and structures. We shall consider

these linguistic forms here as indicators of potential presuppositions, which can only become

actual presuppositions in contexts with speakers.

As already illustrated in. examples [І] to [3], the possessive construction in English is

associated with a presupposition of ex-istence. The existential presupposition is not only

assumed to be present in possessive constructions (for example, 'your car' » 'you have a car'),

but more generally in any definite noun phrase. By using any of the expressions in [5], the

speaker is assumed to be committed to the existence of the entities named.

[5] the King of Sweden, the cat, the girl next door,

the Counting Crows

We shall reconsider the basis of existential presuppositions later, but first we should

note that there was a different type of presupposition present in [4]. In [4], the verb 'know'

occurs in a structure, 'Everybody knows that q', with q as the presupposi-tion. The

presupposed information following a verb like 'know' can be treated as a fact, and is described

as a factive presupposition. A number of other verbs, such as 'realize' in [6a.] and 'regret' in

[6b.], as well as phrases involving 'be' with 'aware' [6c.], 'odd' [6d.], and 'glad' [6e.] have factive

presuppositions.

[6] a. She didn't realize he was ill. (» He was ill)

b. We regret telling him. (» We told him)

c. I wasn't aware that she was