Page 89 - 6688

P. 89

89

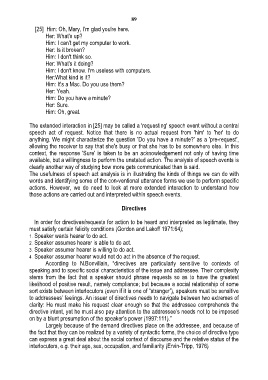

[25] Him: Oh, Mary, I'm glad you're here.

Her: What's up?

Him: I can't get my computer to work.

Her: Is it broken?

Him: I don't think so.

Her: What's it doing?

Him: I don't know. I'm useless with computers.

Her:What kind is it?

Him: It's a Mac. Do you use them?

Her: Yeah.

Him: Do you have a minute?

Her: Sure.

Him: Oh, great.

The extended interaction in [25] may be called a 'requesting' speech event without a central

speech act of request. Notice that there is no actual request from 'him' to 'her' to do

anything. We might characterize the question 'Do you have a minute?' as a 'pre-request',

allowing the receiver to say that she's busy or that she has to be somewhere else. In this

context, the response 'Sure' is taken to be an acknowledgement not only of having time

available, but a willingness to perform the unstated action. The analysis of speech events is

clearly another way of studying bow more gets communicated than is said.

The usefulness of speech act analysis is in illustrating the kinds of things we can do with

words and identifying some of the con-ventional utterance forms we use to perform specific

actions. However, we do need to look at more extended interaction to understand how

those actions are carried out and interpreted within speech events.

Directives

In order for directives/requests for action to be heard and interpreted as legitimate, they

must satisfy certain felicity conditions (Gordon and Lakoff 1971:64);

1. Speaker wants hearer to do act.

2. Speaker assumes hearer is able to do act.

3. Speaker assumer hearer is willing to do act.

4. Speaker assumer hearer would not do act in the absence of the request.

According to N.Bonvillain, “directives are particularly sensitive to contexts of

speaking and to specific social characteristics of the issue and addressee. Their complexity

stems from the fact that a speaker should phrase requests so as to have the greatest

likelihood of positive result, namely compliance; but because a social relationship of some

sort exists between interlocutors (even if it is one of “stranger”), speakers must be sensitive

to addressees’ feelings. An issuer of directives needs to navigate between two extremes of

clarity: He must make his request clear enough so that the addressee comprehends the

directive intent, yet he must also pay attention to the addressee’s needs not to be imposed

on by a blunt presumption of the speaker’s power (1997:111).”

Largely because of the demand directives place on the addressee, and because of

the fact that they can be realized by a variety of syntactic forms, the choice of directive type

can express a great deal about the social context of discourse and the relative status of the

interlocuters, e.g. their age, sex, occupation, and familiarity (Ervin-Tripp, 1976)