Page 84 - 6688

P. 84

84

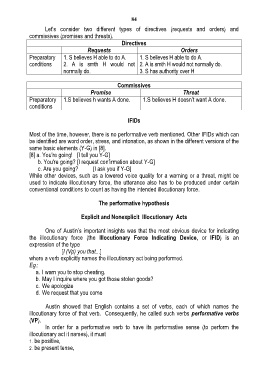

Let’s consider two different types of directives (requests and orders) and

commissives (promises and threats).

Directives

Requests Orders

Preparatory 1. S believes H able to do A. 1. S believes H able to do A.

conditions 2. A is smth H would not 2. A is smth H would not normally do.

normally do. 3. S has authority over H

Commissives

Promise Threat

Preparatory 1.S believes h wants A done. 1.S believes H doesn’t want A done.

conditions

IFIDS

Most of the time, however, there is no performative verb mentioned. Other IFIDs which can

be identified are word order, stress, and intonation, as shown in the different versions of the

same basic elements (Y-G) in [8].

[8] a. You're going! [I tell you Y-G]

b. You're going? [I request confirmation about Y-G]

c. Are you going? [I ask you if Y-G]

While other devices, such as a lowered voice quality for a warning or a threat, might be

used to indicate illocutionary force, the utterance also has to be produced under certain

conventional conditions to count as having the intended illocutionary force.

The performative hypothesis

Explicit and Nonexplicit Illocutionary Acts

One of Austin’s important insights was that the most obvious device for indicating

the illocutionary force (the Illocutionary Force Indicating Device, or IFID) is an

expression of the type

[I (Vp) you that...]

where a verb explicitly names the illocutionary act being performed.

Eg.:

a. I warn you to stop cheating.

b. May I inquire where you got those stolen goods?

c. We apologize

d. We request that you come

Austin showed that English contains a set of verbs, each of which names the

illocutionary force of that verb. Consequently, he called such verbs performative verbs

(VP).

In order for a performative verb to have its performative sense (to perform the

illocutionary act it names), it must

1. be positive,

2. be present tense,