Page 89 - 4498

P. 89

discontinuously, as a result of some external condition, such as

temperature, pressure, and others. For example, a liquid may become gas

upon heating to the boiling point, resulting in an abrupt change in volume.

The measurement of the external conditions at which the transformation

occurs is termed the phase transition. Phase transitions are common in

nature and used today in many technologies.

In the modern classification scheme, phase transitions are divided into two

broad categories.

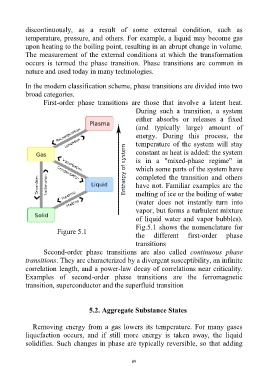

First-order phase transitions are those that involve a latent heat.

During such a transition, a system

either absorbs or releases a fixed

(and typically large) amount of

energy. During this process, the

temperature of the system will stay

constant as heat is added: the system

is in a "mixed-phase regime" in

which some parts of the system have

completed the transition and others

have not. Familiar examples are the

melting of ice or the boiling of water

(water does not instantly turn into

vapor, but forms a turbulent mixture

of liquid water and vapor bubbles).

Fig.5.1 shows the nomenclature for

Figure 5.1

the different first-order phase

transitions

Second-order phase transitions are also called continuous phase

transitions. They are characterized by a divergent susceptibility, an infinite

correlation length, and a power-law decay of correlations near criticality.

Examples of second-order phase transitions are the ferromagnetic

transition, superconductor and the superfluid transition

5.2. Aggregate Substance States

Removing energy from a gas lowers its temperature. For many gases

liquefaction occurs, and if still more energy is taken away, the liquid

solidifies. Such changes in phase are typically reversible, so that adding

89