Page 18 - 6689

P. 18

17

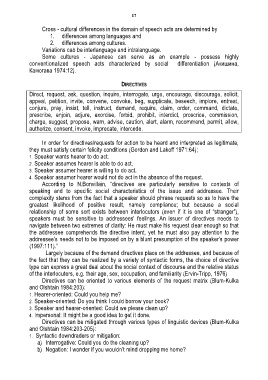

Cross - cultural differences in the domain of speech acts are determined by

1. differences among languages and

2. differences among cultures.

Variations cab be interlanguage and intralanguage.

Some cultures - Japanese can serve as an example - possess highly

conventionalized speech acts characterized by social differentiation (Акишина,

Камогава 1974:12).

DIRECTIVES

Direct, request, ask, question, inquire, interrogate, urge, encourage, discourage, solicit,

appeal, petition, invite, convene, convoke, beg, supplicate, beseech, implore, entreat,

conjure, pray, insist, tell, instruct, demand, require, claim, order, command, dictate,

prescribe, enjoin, adjure, exorcise, forbid, prohibit, interdict, proscrice, commission,

charge, suggest, propose, warn, advise, caution, alert, alarm, recommend, permit, allow,

authorize, consent, invoke, imprecate, intercede.

In order for directives/requests for action to be heard and interpreted as legitimate,

they must satisfy certain felicity conditions (Gordon and Lakoff 1971:64);

1. Speaker wants hearer to do act.

2. Speaker assumes hearer is able to do act.

3. Speaker assumer hearer is willing to do act.

4. Speaker assumer hearer would not do act in the absence of the request.

According to N.Bonvillain, “directives are particularly sensitive to contexts of

speaking and to specific social characteristics of the issue and addressee. Their

complexity stems from the fact that a speaker should phrase requests so as to have the

greatest likelihood of positive result, namely compliance; but because a social

relationship of some sort exists between interlocutors (even if it is one of “stranger”),

speakers must be sensitive to addressees’ feelings. An issuer of directives needs to

navigate between two extremes of clarity: He must make his request clear enough so that

the addressee comprehends the directive intent, yet he must also pay attention to the

addressee’s needs not to be imposed on by a blunt presumption of the speaker’s power

(1997:111).”

Largely because of the demand directives place on the addressee, and because of

the fact that they can be realized by a variety of syntactic forms, the choice of directive

type can express a great deal about the social context of discourse and the relative status

of the interlocuters, e.g. their age, sex, occupation, and familiarity (Ervin-Tripp, 1976)

Directives can be oriented to various elements of the request matrix (Blum-Kulka

and Olshtain 1984:203):

1. Hearer-oriented: Could you help me?

2. Speaker-oriented: Do you think I could borrow your book?

3. Speaker and hearer-oriented: Could we please clean up?

4. Impersonal: It might be a good idea to get it done.

Directives can be mitigated through various types of linguistic devices (Blum-Kulka

and Olshtain 1984:203-205):

1. Syntactic downdraders or mitigation:

a) Interrogative: Could you do the cleaning up?

b) Negation: I wonder if you wouldn’t mind dropping me home?