Page 33 - 4952

P. 33

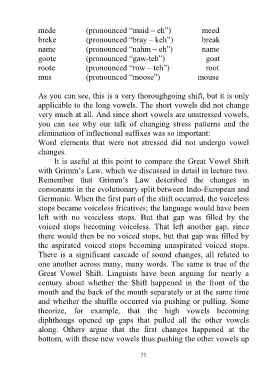

mede (pronounced “maid – eh”) meed

breke (pronounced “bray – keh”) break

name (pronounced “nahm – eh”) name

goote (pronounced “gaw-teh”) goat

roote (pronounced “row – teh”) root

mus (pronounced “moose”) mouse

As you can see, this is a very thoroughgoing shift, but it is only

applicable to the long vowels. The short vowels did not change

very much at all. And since short vowels are unstressed vowels,

you can see why our talk of changing stress patterns and the

elimination of inflectional suffixes was so important:

Word elements that were not stressed did not undergo vowel

changes.

It is useful at this point to compare the Great Vowel Shift

with Grimm’s Law, which we discussed in detail in lecture two.

Remember that Grimm’s Law described the changes in

consonants in the evolutionary split between Indo-European and

Germanic. When the first part of the shift occurred, the voiceless

stops became voiceless fricatives; the language would have been

left with no voiceless stops. But that gap was filled by the

voiced stops becoming voiceless. That left another gap, since

there would then be no voiced stops, but that gap was filled by

the aspirated voiced stops becoming unaspirated voiced stops.

There is a significant cascade of sound changes, all related to

one another across many, many words. The same is true of the

Great Vowel Shift. Linguists have been arguing for nearly a

century about whether the Shift happened in the front of the

mouth and the back of the mouth separately or at the same time

and whether the shuffle occurred via pushing or pulling. Some

theorize, for example, that the high vowels becoming

diphthongs opened up gaps that pulled all the other vowels

along. Others argue that the first changes happened at the

bottom, with these new vowels thus pushing the other vowels up

31